|

|

|

|

|

|

|

home

about

Protz

features

A-Z

books

|

|

Protz:

features

reviews

tastings

news & events

books

|

| |

Clean bowled by Cooper's

by Willard Clarke, 05/2009

Cooper's brewery in Adelaide has beautifully sculpted lawns decorated with gum trees. Is this an elaborate joke? The company used to be laughed to derision in Australia for concentrating on ale and in particular cloudy ale. Cooper's, it could be said, was up a gum tree.

But the family-owned brewery has had the last laugh. It's a flourishing company. It has broken out of its South Australia heartland and now enjoys national sales. It exports widely and its bottled beers are available in Britain.

|

|

|

It's run by the fifth generation of the Cooper family who believe firmly in tradition and quality. When brewing giant Lion Nathan, owner of Castlemaine, attempted to buy Cooper's in 2005, 94.6 per cent of the 117 shareholders, mainly family members, turned down an offer worth 450 million Australian dollars - that's around �200 million.

In the politest possible way, the Coopers told Lion Nathan they couldn't give a XXXX for its offer. "That figure of 94.6 per cent has become almost as famous as Don Bradman's batting average," operations director Nick Sterenberg said. They take such matters seriously in Adelaide: I drove down Sir Donald Bradman Boulevard on my way to the brewery while the post box number for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is 99.8, the Don's astonishing average.

|

|

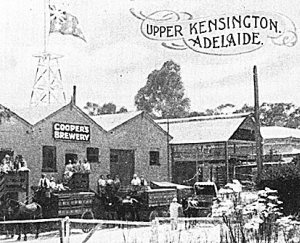

Cooper's dates from 1862. It was founded by a Yorkshireman, Thomas Cooper, who had emigrated from Skipton with his wife, the daughter of an innkeeper. While Thomas worked as a dairyman and a cobbler, his wife brewed beer at home. When she became ill, Thomas tried his hand at making beer. Not only was his wife cured, but friends of the family raved about Thomas's beer and told him he should open a brewery.

For most of its life, the brewery was based in the Leabrook district of Adelaide.

|

It used a brewing method similar to the Burton Unions here: primary fermentation took place in vessels made from the hardwood jarrah. The beer was then dropped into wooden puncheons or hogsheads where it continued to ferment and mature.

In 2001, Cooper's moved to a new site at Regency Park. There were two reasons behind the move: the brewery needed more capacity while Leabrook had become a posh suburb, home to doctors and lawyers who objected vociferously to having a brewery in their midst.

Leabrook could produce 700,000 hectolitres a year while Regency Park has a potential capacity of 250 million hectos. It's typical of the Cooper family that the big, bright and traditional brewhouse, based on mash tuns, mash filters and coppers, was designed by Briggs of Burton-on-Trent, in the heartland of English pale ale brewing. The old vessels from Leabrook are held in a museum on site, packed with fascinating artefacts of brewing in the 19th and 20th centuries. There's a nice touch in the boardroom, where the conference table is built from jarrah wood from the original site.

"We brew an ancient sort of beer - it was old in 1862," Nick Sterenberg says. He's a Brit by birth and worked for Courage and Charles Wells before moving to Australia, where he now speaks with an undiluted local accent. "The Coopers are unswayed by fashion. In the 1980's, Bill and Maxwell Cooper developed markets outside South Australia, using the slogan �cloudy but fine'."

While the brewery's main beer, Pale Ale (4.5%), is hazy rather than cloudy, the flagship beer, Sparkling Ale (5.8%), belies the name. It takes a certain kind of chutzpah in Australia to deliberately produce a beer called sparkling that is opaque in the glass. Part of the skill of the brewers at Cooper's is to make a beer that keeps yeast in suspension during fermentation and conditioning. The present generation of Coopers, Glenn and Tim, brew what they call "a significantly different beer". It has been taken up with enthusiasm by younger drinkers, university students in particular,

"We have very loyal drinkers," Nick says. "We have a Cooper's Club where drinkers pay for a regular newsletter."

|

|

|

Glenn and Tim Cooper are in the brewery every day, hands-on and committed. They are not resting on ancient laurels but are running an expanding business. Malt extract accounts for around half of the brewery's production. Some of it goes to cereal and confectionery manufacturers but the bulk is turned into home-brewing kits. Cooper's is the undisputed biggest producer of brewing kits - 2.5 million cans a year -- on the planet and exports to many countries, including Scandinavia and Britain.

"Our kits are popular in countries where beer tax is high," Nick Sterenberg laughs.

The company is also developing new styles of beer. It brews its own lager, makes a wonderful oily, creamy stout and has recently introduced Mild (3.8 %) and Dark Ale (4.5%), which has a fine roasted malt and chocolate character. In the late 1990s, it started to make an annual Vintage Ale (7.5%), with massive vinous fruit and bitter hops character.

Draught beer is only a quarter of annual production. Bottles are filled direct from conditioning tanks. Unlike Worthington's White Shield here, which has a similar history to Cooper's, based on mid-19th century pale ale, the Adelaide beers are not filtered or re-seeded with different yeast. The yeast strain is powdery, which helps explain why it doesn't settle in bottle and gives Sparkling Ale its cloudy appearance.

|

|

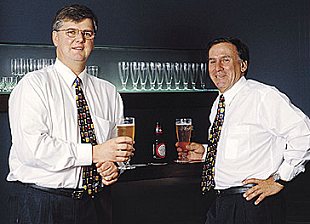

I may have helped restore another tradition. Glenn Cooper (pictured on right, alongside Tim Cooper) and Nick Sterenberg took me for lunch in their shop-window pub, the Cooper's Alehouse. As well as a spacious bar serving the brewery's full range, there's an attractive restaurant. When I spotted that oysters were available, I suggested matching the seafood with Cooper's Stout, in the Irish manner. Glenn and Nick enjoyed the tasting and oysters and stout may become a regular on the pub's menu.

|

But they won't be naming a boulevard in Adelaide in my honour just yet. I have to improve my batting average first.

|

|

home

about

Protz

features

A-Z

books

|